Ross Driedger

Developing Your Bridge Memory

Introduction

Visualization and memory are vital skills to the bridge player. A declarer must remember what cards have been played, what remains in the hands of the defenders and whether certain cards have become tricks or require further work to develop. This just not includes the honour cards, but the spots, as well. Very often in the play of a suit, the honours will be played early. Declarer must know if, say, an 8 is high and if not, which higher cards are still out. Early in a hand, a good declarer will be able to visualize much of the original holdings of the defenders and then compare their actions to what they are likely to hold.

Declarer’s task is easy in comparison to what the defenders face. Not only do they have to visualize, they must compare what they can construct and check their work to an auction that the opponents had. Each defender must then communicate what they know to their partner (in legal ways, of course). It is no wonder that defense is considered the most difficult part of the game.

Playing bridge without visualization is like playing tennis blindfolded. No one would consider going on to the tennis court to play with a scarf wrapped around the eyes. Yet every day, people play bridge without drawing inferences from the bidding and the progression of tricks. No surprise, if you think about it: developing visualization and memory skills required practice and work – and who wants to work? The very good news is that if you are an intermediate player who hasn’t learned to visualize the hands as you play bridge, a little effort and practice will go a long way to improving your game.

Disclaimer

Many bridge players are aging, and with that, in some cases, come with physiological problems. For those who are struggling with these afflictions, memory is a challenge and this lesson makes no claims about improving the memory of people who are suffering from one of these conditions.

Bulking Up Your Brain

For the rest of us, especially many who jokingly suffer from ‘senior moments’, an improved memory can be developed. We live in a society where we live in patterns developed over years of repetition. We don’t need to actively recall how to drive a car, toast your morning bagel, or tie our shoes – we’ve been doing this for decades and the brain has recalled these habits to such a point that we don’t actively think about how to do it.

Add to that, we live in a technology age where many of us carry around phones or tablets that have more computing power than an expensive desk-top computer of ten years ago. Don’t you remember your favourite cookie recipe? Look it up on your phone. You can’t quite remember how to get to that great little woodworking shop? Put the address into your GPS unit and it will tell you the best route to take, considering the volume of traffic, and give you an accurate estimated time of arrival. You don’t have to remember to pay that hydro bill: your banking app will do that automatically.

Years of habits and the technology we have make living our lives easier without having to remember all the little details.

What happens? Unless there are physiological problems, our memory is like a muscle; if you don’t exercise it, it atrophies and grows flabby. We can go through our lives relying on our habits or writing down important information or looking it up on the Internet. Developing memory seems like an effort, especially when we play dozens of hands in the course of a day. Once one board is finished, we must make the effort to visualize and memorize another deal.

The good news is that, given a healthy brain, we can improve and develop our memory skills.

What Kind of Memory?

The modern model of memory makes three distinctions in kinds of memory:

- Short Term Memory: is the capacity for holding, but not manipulating, a small amount of information in the mind in an active, readily available state for a short period of time. The time span will be in the order of seconds. If someone asked you to dial a phone number, you would likely recall it for the few seconds required to punch in the numbers and then forget it. A healthy person can hold four or five pieces of information in short term memory.

- Working Memory: is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that is responsible for temporarily holding information available for processing or manipulation. It is closely related to short term memory, but it is retained for the purposes of that processing. Because it is involved in manipulation, more information can be held in working than in short term memory. It is heavily used in decision making. Once the processing has been done and a decision made, the mind will likely release that information.

- Long Term Memory: This is the retention of information, feelings and emotions for an indefinite time.

There are different kinds of memory; some people can memorize numbers, but can’t remember the name of someone introduced to them five minutes prior. Others can memorize pages of text (like a Shakespearean actor), yet cannot remember where they left their car keys -- or even their car!

There are even Competitive Memory Games, where contestants can earn the title of Grand Master of Memory. In order to earn this, people had to be able to successfully negotiate the following three memory feats:

- Memorize 1,000 random digits in an hour,

- Memorize the order of 10 decks of cards in an hour, and

- Memorize the order of one deck of cards in less than two minutes.

As impressive as these skills are, would these skills really improve one’s ability to play bridge?

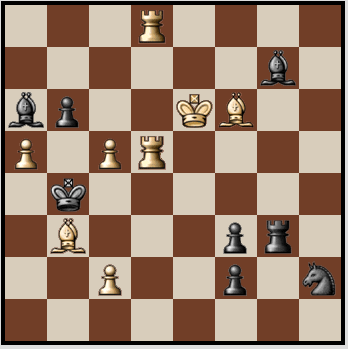

In the 1950s and 60s, the Dutch psychologist, and chess master, Adriaan de Groot conducted a number of experiments dealing with memory and decision making. In one experiment, he had a group of chess masters (the ‘test group’) and a group of people of similar intelligence that did not play chess (the ‘control group’). In the first part of the experiment, each participant in both groups was presented with a set of chessboard positions taken from tournament play. The individuals were asked to memorize the positions as best they could and, after some time, they were asked to reproduce the positions that they had seen. The control group (non-chess players) struggled to remember the positions, while the test group was far more successful – some of them having perfect recall of all the positions they were given.

In the second part of the test, the positions consisted of random placement of pieces on a chessboard. Some of these positions were not even legal within the rules of the game. The result? Members of control group remained about the same as they were in the first part of the test, while the success for those in the test group fell to roughly the same level as the others.

So what conclusions were drawn? Why did the chess players do so much better in the first part of the experiment than the second? de Groot hypothesized (without any serious dissention from others) that the chess players could remember the actual chess positions because they applied tactical and strategic principles of chess to the positions from tournament play. The board positions made ‘chess sense’ and using that sense allowed the chess players to easily reconstruct the details of each example. The control group members could not use these tools because they did not have the developed skills to analyze the positions as did the members of the test group. When the ‘chess sense’ was removed from the examples (the second part of the test), the test group members had trouble remembering the board positions.

It is not enough to memorize the location of all the cards in a deal. If that were the case, then those with an eidetic memory would be exceptional bridge players. There are many world class bridge players whose memory could not be described as eidetic.

Developing a successful bridge memory requires bringing the tactical and strategic parts of the bridge mind.

The keys to a good bridge memory include:- Compartmentalization or Chunking. The ability to separate the suits individually in the mind is crucial. A good bridge memory will be able to switch considerations from one suit to another.

- Concentration. A player who is concentrating will notice which cards have shown up and where. Being a social game, bridge encourages interaction between players. Catching up with an acquaintance before a hand can lead to distraction as the hand is being bid and played. Many top experts are as social as anyone else, but when they are playing, they pay attention to what is happening at the table.

- Counting. Two immutable and unchanging pieces of information is with all players from the start of the hand to the end: each suit has 13 cards and each hand starts with 13 cards. Many beginning and intermediate players do not take advantage of these axioms. In addition, there is the related information that all hands of each deal total 40 High Card Points (HCP). Counting out a hand or HCP is really not very difficult to do: the important part is to be in practice to do it and not to get lazy.

- Putting the hand together. In visualizing a hand, it is important to remember that all four hands fit together to form one deal. Each hand does not exist in a vacuum. It is related to the other three. A player can remember the auction and visualize how the hands work together to produce the tricks that make or set the contract is ahead of the memory game.

A good, even great, bridge memory is something that can be developed through practice exercises and concentration. It does require work, but the payoff is the measurable and distinct improvement as a bridge player.

Perhaps a word of warning is not out of place: As your visualization and memory skills improve, you will start noticing your partners who are not working on their skills. They will not make the plays that now seem obvious to you. You need to decide how patient and tolerant of this you need to be. The best solution, of course, is to go through these exercises with your regular partner. This will dramatically improve your results, whether you play for fun, masterpoints or money.

Memory Exercises

"13s" or "Distributions"

This exercise is one of the foundational skills for bridge players. It is quite simple, but its application should be second nature. Given three numbers, the fourth, such that the sum of all four equals thirteen, should immediate apparent. Suppose the first three numbers are 4, 4, 2, this exercise immediately gives the number 3 (4 + 4 + 2 + 3 = 13). The reason for this exercise should be obvious: once a player knows the count of three suits of a hand, then the number of the fourth automatically comes to mind. This also applies to the distribution of one suit around the table: if you know the starting count of your hand, dummy (both immediately obvious), if you get the starting count on a third hand, you will know the starting count on the fourth.

Here are some examples:

- 2 + 4 + 2 + x = 13 (x is 5)

- 0 + 5 + 4 + x = 13 (x is 4)

- 2 + 3 + 2 + x = 13 (x is 6)

- 1 + 5 + 4 + x = 13 (x is 3)

- 4 + 4 + 4 + x = 13 (x is 1)

- 2 + 6 + 5 + x = 13 (x is 0)

Mastering this as a basic reflex will save a good deal of time: as soon as you know three numbers, the fourth should occur to you without conscious thought.

When experienced bridge players talk about distributions of cards, either within a hand or a suit around the four hands at the table, they will use a set of four numbers that add up to 13 to describe them. Distributions can be either general or specific, and each will be notated differently when written down.

General Distribution

When describing the basic shape of a hand, we might say a hand is a 4-4-3-2 shape. When written this way, it denotes a shape when one suit is four cards long, as is another, the third suit has three cards and the remaining suit has only two. No number is specifically tied to one suit. The following hands would qualify as 4-4-3-2:

- ♠: QJ63 ♥: AQ92 ♦: 987 ♣: QJ

- ♠: 42 ♥: JT74 ♦: 432 ♣: AKT4

- ♠: 932 ♥: 64 ♦: 6432 ♣: 8743

When giving a general distribution, the longest suit is given first, followed by the second longest, the third and then the shortest. For example, a hand’s general distribution would be 5-4-3-1, not 3-4-1-5. A 7-2-2-2 hand would not be described as 2-2-7-2.

Specific Distributions

More commonly, a specific distribution is given. It is similar to a general distribution, except that the first number corresponds with the Spade suit, the second to the Hearts, the third to the Diamonds and the last to the Clubs. It is spoken in the same way as a general distribution, but it is written with equal signs instead of hyphens. A 5=3=4=1 shape indicates that the hand under discussion has five Spades, three Hearts, four Diamonds and a singleton Club.

In a discussion, which distribution is clear in context. "I generally don’t like pre-empting with a 7-2-2-2", someone might say, mentioning a distribution that offers some disadvantages to opening the bidding at the 3 level. The comment does not mean that the seven card suit is necessarily Spades. The comment implies that it could be any of the suits.

"What do you open with 13 HCP and 2=2=4=5?" The question describes a problem hand shape in standard and 2/1 bidding. In this context, the hand has two ♠s and ♥s, four ♦s and five ♣s. This is very often the opening question when two experienced players start discussing the meaning of reverse bids. If you are unfamiliar with reverse bids, ask your bidding teacher.

For the sake of the discussion of memory and distribution, we will be using specific distributions.

"13s" Practice

You will be given three numbers. Choose the number that completes the specific distribution.

"40s"

This is another activity that should be come reflexive for the bridge player. After the opening lead, all players know the point count in two of the four hands. While HCP are an inaccurate measure of a hand's playing strength on distributional deals, one of the keys to effective defense and declarer play is to pinpoint the likely locations of the hidden high cards. Factoring the missing high cards into the auction can clearly pinpoint the layout of the deal.

This exercise is similar to the "13s", except the target number is 40. Suppose you are given the three numbers: 13, 7 and 11. In the 40s exercise, you add the three numbers together (31), subtract from 40 to get 9.

Here are some examples:

- 12 + 5 + 12 + x = 40 (x is 11)

- 9 + 9 + 9 + x = 40 (x is 13)

- 8 + 11 + 12 + x = 40 (x is 9)

- 10 + 9 + 4 + x = 40 (x is 17)

- 12 + 7 + 11 + x = 40 (x is 10)

- 6 + 1 + 7 + x = 40 (x is 26)

"40s" Practice

You will be given three numbers. Choose the number that completes the HCP distribution.

An Alternative Way of Counting

Counting three hands, subtracting the sum from 40 can be tedious, so here is an alternative method that some find easier:

You are playing a round of golf that is four holes long. Each hole is a par 10, so par for the whole course is par 40. Further, you are a very consistent golfer, so you will shoot par after all four holes have been played.

Starting with the first hole, you score the number of high cards points. Calculate your score with respect to par 10: If the hand has 12 HCP, you are 2 over par; if 5 HCP, you are 5 under par; if 10, you are even par on that hole.

Do the same thing for the second hand, keeping track of your score in terms of par.

Repeat this for the third hand.

To determine the HCP count of the fourth hand, remember that you will score even par for the round of golf. So if, for example you are 4 under par after three holes, you will score 4 over par for the last hole. 10 (par) plus 4 will put you at par for the course. The fourth hand has 14 HCP.

- 12 + 5 + 12 + x = 40

- +2 -5 (-3) +2 (-1): +1 on the fourth hole: 11.

- 9 + 9 + 9 + x = 40

- -1 -1 (-2) -2 (-3): +3 on the fourth hole: 13.

- 8 + 11 + 12 + x = 40

- -2 +1 (-1) +2 (+1): -1 on the fourth hole: 9.

- 10 + 9 + 4 + x = 40

- 0 -1 (-1) -6 (-7): +7 on the fourth hole: 17.

- 12 + 7 + 11 + x = 40

- +2 -3 (-1) +1 (0): Par on the fourth hole: 10.

- 6 + 1 + 7 + x = 40

- -4 -9 (-13) -3 (-16): +16 on the fourth hole: 26.

"The Exercise"

"The Exercise" is graduated practice in remembering the bridge aspects of the deal of 52 cards. There are a number of levels; the first starting out very simply and progressing to the complete memorization and visualization of a bridge hand.

The point of doing them is not perfection. If you were perfect, you would not need "The Exercise". Even with practice you will make errors, but it is in the making and discovery of the errors that your skills will improve and improve dramatically. Do not feel pressure to move to the next level unless you are comfortable with your performance on the present one. There are also ways of adjusting the difficulty within each level.

Think of this as the memory version of going to the health club to get into shape. If you are out of shape, your personal trainer is going to give you exercises that stretch your abilities, get you working up a bit of a sweat and raise your heart rate – but not too much. You cannot expect to match the performance of the guy who has been working out for ten years and has 6% body fat. When you start "The Exercise" you cannot realistically expect to have the memory of a world class player who has been playing expert bridge in big events for twenty-five years. Challenge yourself to improve and acknowledge your progress but don’t expect overnight rapid success. You, like most of us, probably have a lot of lazy mental habits to overcome – it is only human.

"The Exercise" works best if you do a little bit each day. Practicing for fifteen minutes each day for a week will be of much greater benefit that doing two hours a day once a week. This will help you get into the habit of applying your memory and visualization on each hand instead of having to remember to do it. Many small increments of work on "The Exercise" are much more productive than a few big sessions.

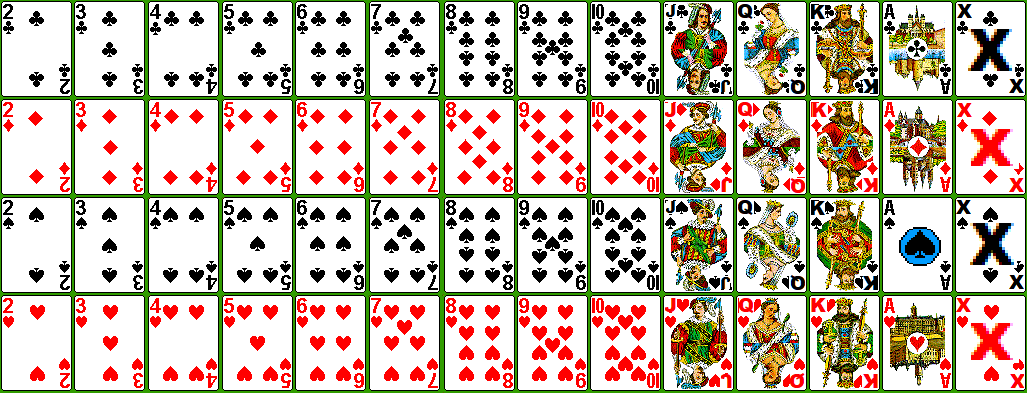

All you need to do "The Exercise" is a deck of cards and, optionally, a pen and a paper to write down a visualized hand.

Shuffle and deal a deck of cards into four bridge hands. You can take thirteen cards off the top of the deck for each hand or deal them out one at a time as you would at the table. Take a look at the first three hands in turn and commit some aspect or aspects of each hand to memory. The aspects of each hand are what determine the difficulty of each level and each aspect is bridge related in order to make the aspect more than just trivial data.

Once a hand’s aspects have been committed to memory, it is put face down on the table and you are not allowed to pick it up again – the hand is said to be buried – even though you are expected to remember the aspects of each hand. You cannot move on to the next hand until the present hand is buried. After the first three hands have been buried, "The Exercise" is to recreate the aspects of the fourth, hidden hand based on what you remember of the first three. Examine the fourth hand to confirm your visualization and memory of the first three hands.

The first level is to remember each hand's HCP. You pick up the first hand, count and remember the hand's HCP. Once you feel confident in recalling the hand’s strength, bury the hand. Keep in mind that a buried hand cannot be examined again and you cannot pick up the next hand until you have buried the previous. Once the first hand has been buried, pick up the second hand, count and remember the HCP. When you feel confident that you can recall the HCP, bury the hand. With two hands’ HCP committed to memory and buried, pick up the third hand and count its HCP. Bury the third hand.

It is helpful when burying a hand to review all the buried hands in your mind. This helps to visualize the hands to see how they fit together.

After burying the first three hands, visualize the HCP missing from them and calculate the points that are held by the fourth. It is a simple calculation: sum the HCP from the first three hands and subtract the total from 40. Examine the fourth hand to confirm the strength of the hand. If you are in error, re-examine the other hands to find your mistake.

At this level, each hand of "The Exercise" will take a few minutes so it is easy to do this five times within fifteen minutes. It really is a simple thing to do, yet how often do we play a bridge hand where we don’t count the points, even if we are defending against a declarer that opened the bidding with 1NT?

The Levels

Each level increases the difficulty of "The Exercise" but concentrating on different aspects of the hands. It is recommended that you practice each level until you can complete a deal within about five minutes. This will take some practice, but it is a worthwhile investment into your bridge future.

- Level 1: HCP

- Level 2: Specific distribution of all four suits. Use specific distributions to describe the hands. A deal may be: Hand 1: 5=1=4=3; Hand 2: 1=4=4=4; Hand 3: 5=5=2=1. Hand 4 is 2=3=3=5.

- Level 3: HCP and specific distributions.

- Level 4: Number of honours. Recall the numbers of honours of each hand as the number of Aces=Kings=Queens=Jacks=Tens. A hand may be: Hand 1: 1=0=1=2=0; Hand 2: 2=0=0=1=3; Hand 3: 0=3=3=0=1. Hand 4 is 1=1=0=1=0.

- Level 5: Level 2 + Level 4.

- Level 6: Specific honours and distribution in each suit. All other cards are considered equal and given a designation of 'x'.

- Level 7: As in Level 6, recalling all cards down to the 8 spot.

- Level 8: As in Level 7, recalling all cards down to the 6 spot.

- Level 9: Recall and placing all 52 cards.

The goal is to complete a deal within five minutes, regardless of level. The lower levels are very helpful and offer good scope for improvement for the intermediate and advanced player. Level 9 is what would be expected by a world class bridge player.

You can practice "The Exercise" Here

Adjustments in Difficulty

Each level can be made more or less difficult by using slightly different techniques.

Easier

Remembering the details of three hands can be challenging, especially if you are moving up a level. If, in moving up a level, you find that the deals have become too difficult, you can make this temporary modification: Study and bury the first two hands as usual, but construct the fourth hand while you are looking at the third.

Suppose you have started working at Level 2. The first hand has a 5=2=2=4 shape; you have committed this to memory and buried the hand. The second hand is 4=2=3=4. After you bury the second hand, the third hand reveals itself as 1=4=4=4. Without burying the third hand, you deduce that the fourth hand is 3=5=4=1.

I would recommend this as a temporary measure, until you develop enough skill and confidence to bury the third hand, as usual. You might be willing to say: “But when we play bridge, we get to look at, not just one hand, but two. Why commit the third hand to memory?” The point of "The Exercise" is to develop the memory skills. Being able to remember and visualize all four hands puts you at a great advantage to those who cannot or won’t do this.

Harder

Once you develop some basic skills in bridge, we start playing quickly – too quickly. This is especially the case when playing against a fast player. It is important that you don’t get swept up in their tempo. Play regularly, but at your pace.

One way to slow down your play is to not sort your hand!

What happens when you do this? You need to concentrate on the cards you hold. You stop playing by reflex and you have to think about what you have. I am always somewhat amused players that will stare at their cards when thinking about what to bid or play. By not letting your thought process just process what you are holding, you are forced to think about the hand as a whole. I recommend you try this when you play, just for a hand or two to see what happens to your concentration and visualization.

But for now, try doing "The Exercise" without sorting the hands. It adds an extra challenge to the deals, but it will improve your concentration.

"What's Missing"

This exercise fits well between Levels 5 and 5 of "The Exercise".

Extract all the cards of one suit from a deck and shuffle them up as best you can. Make four piles of cards, face down. It is generally best to use a balanced distribution. Shapes like 4-4-3-2 or 4-3-3-3 work well. Pick up the first pile and memorize the cards. When you are sure of the holding, bury the cards and pick up the second pile, memorize and bury these cards. Repeat with the third pile. Once that is buried, visualize the fourth, unseen pile of cards.

- Level 1: Consider each honour card specifically. All spot cards are considered as an 'x'.

- Level 2: Consider all cards down to the 8. All lower cards are considered as an 'x'.

- Level 3: Consider all cards down to the 6. All lower cards are considered as an 'x'.

- Level 4: Consider all cards in a suit.

As an example of Level 1, suppose you divide the cards in piles of three, three, three and four cards. The first pile has Axx, the second has Txx, and the third has Qxx. The goal is to visualize the fourth pile as KJxx.

Level 2 might look like this, using piles of two, three, four and four: the first hand is 9x, the second hand Axx, and the third Kxxx. The fourth pile will be visualized as QJT8.

Level 3, using the distribution of three, one, five and four cards, might be: first pile KJ8, the second just the Q, and the third as A7xxx. The fourth pile is T96x.

In Level four, we consider all cards of the suit. If we divided the cards into piles of three, two, three and five, the cards in each pile might be, first A52, second 87, and third JT6. In this exercise, we would visualize the fourth holding as KQ943.

As with the levels in "The Exercise", it is best to develop a mastery of a level before moving to the next, and this can be done in conjunction with Levels 6, 7, 8 and 9:

- Level 1 of "What's Missing" corresponds to Level 6 of "The Exercise"

- Level 2 of "What's Missing" corresponds to Level 7 of "The Exercise"

- Level 3 of "What's Missing" corresponds to Level 8 of "The Exercise"

- Level 4 of "What's Missing" corresponds to Level 9 of "The Exercise"

"What's Missing" Practice

You will be given the suit holding for South, West, and North. .

Visualization is continued of the Visualization page.